On Your Feet Foundation does not take a position on adoption. However, we do advocate for ethical adoption practices through Activism in Adoption. As long as adoption exists, we must work to ensure that every adoption is ethical and that every expectant parent and birthparent is treated with dignity and respect, which includes having full knowledge of their rights and options. Ethical adoptions help to ensure better outcomes for all members of the adoption constellation.

One of the most commonly asked questions about adoption is this: why is it so expensive? Ask this question in adoption circles, and you’ll get the same answer, over and over again: it’s expensive because it is a legal process, which requires the involvement of attorneys, and adoption specialists, and counselors, and social workers; homestudies have to be written and potential adoptive parents have to provide government background checks, and every step of that process costs money, and often, ethics are cited as part of the expense. It costs money to be ethical.

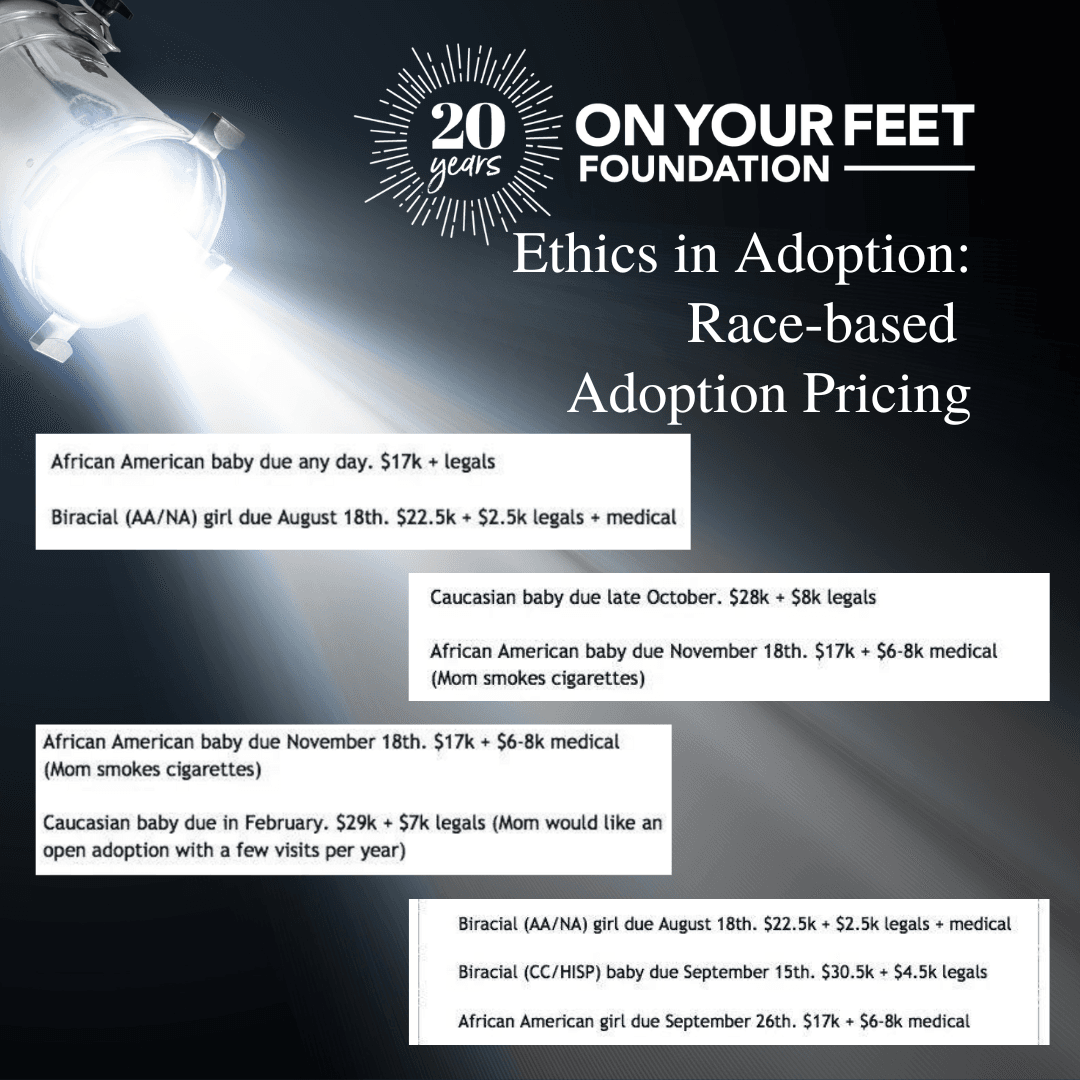

Why, then, is there such a range in the cost of private adoption? If ethical adoption requires the same set of parameters – social workers, homestudies, lawyers for both the birth family and potential adoptive family, adoption professionals, etc – how is it that there is such a wide disparity in cost? It turns out, one of the biggest predicators of adoption costs is the race and gender of the child. Put bluntly, non-white children are a cheaper domestic adoption choice.

Prior to World War II, the guiding philosophy in adoption was matching: finding children whose skin color and religion matched their (predominantly white) potential adoptive parents. Built into this method of adoption was the unspoken tenet that if a child matched well enough with their adoptive parents, it might not even be necessary to tell them they were adopted, completely erasing their history and rewriting it. In 1944, the Boys and Girls Aid Society, witnessing the overabundance of non-white children in need of permanent homes, began promoting interracial adoption. Calling their campaign "Operation Brown Baby,” they began facilitating interracial adoption as a solution. While this was happening, international adoption was also growing, with children predominantly from Asian countries being adopted by white Americans.

As interracial adoption numbers began to grow, concerns were beginning to be raised. In 1972, the National Association of Black Social Workers issued a statement that took “a vehement stand against the placements of black children in white homes for any reason,” calling transracial adoption “unnatural,” “artificial,” “unnecessary,” and proof that African-Americans continued to be assigned to “chattel status.” In the years that followed, transracial adoption slowed, until 1994, when the Multi-Ethnic Placement Act (MEPA) was enacted “to decrease the length of time that children wait to be adopted; to prevent discrimination in the placement of children on the basis of race, color, or national origin; and to facilitate the identification and recruitment of foster and adoptive parents who can meet children’s needs.”

This is a very simplified overview of 80 years of complex adoption history, and teasing out the nuance in the history of interracial adoption is better suited to a book than a blog post. But it does set the stage for how our society has thought about adoption, and interracial adoption in this country, and it serves as a reminder that one of the core tenets of adoption should be that it is child-centered; that the needs of the child come first, always.

However, when adoption price-tags vary based on the gender and race of a child, adoption functions as a practice run like a marketplace, in which children can be priced individually or in race-based categories based on market preference. NYU Stern School economist Allan Collard-Wexler, when writing about adoption and adoption costs, found that the most requested preference from adoptive parents was a white, assigned female at birth infant, concluding that, “the cost of adopting a black baby needs to be $38,000 lower than the cost of a white baby, in order to make parents indifferent to race.” In a 2013 NPR series, The Race Card Project: Six-Word Essays, correspondent Michele Norris writes, “Non-white children, and black children, in particular, are harder to place in adoptive homes. So the cost is adjusted to provide an incentive for families that might otherwise be locked out of adoption due to cost, as well as 'for families who really have to, maybe have a little bit of prodding to think about adopting across racial lines.'"

Families considering adopting a child are often stunned to discover that the cost of adoption varies by race.

Black babies cost less. My wife and I learned this sitting on a worn couch across from two white women explaining the fee schedule for adoptions. The cost to adopt a newborn black infant was a fraction of that to adopt a white one. At another agency, we were offered a deal on twins — adopt one and get the other at half off. Years before America asked "do black lives matter?" I could tell you: "Not as much". - Dr. Brian H. Williams

When adoption costs are race-based, two things happen. One, families hoping to adopt may choose interracial adoption only because it is more affordable, which places children into families who may not be willing, or able, to build the tools and skills necessary to parent that child. Successful transracial adoption, at a minimum, requires adoptive parents to dedicate themselves to becoming anti-racist, to be willing to have uncomfortable conversations, to be proactive in seeking out racial mirrors and mentors, and to be committed to lifelong learning. Discounting children based on their race does nothing to encourage any of that work, and we see how this plays out in the lives of transracial adoptees every day. Abby Johnson, a noted antiabortion activist who spoke at the Republican National Convention, casually commenting in a YouTube video that, police would be well-advised to be wary of her adopted ‘brown son, as he is more likely to commit a violent crime than her two white sons are, is an excellent example of what happens when white parents don’t do the work. Racial profiling, she said, was just statistics. When we started Activism in Adoption education, we made race one of the core pillars, to educate every member of the adoption constellation on what it means for a Black child to come into a white family, so that we can help improve outcomes for those adoptees, and their families. No parent should ever see their sons the way Johnson sees hers, and no Black child should enter a white family because they were the most affordable option.

The second thing that happens is that at some point in their lives, non-white adoptees growing up in white households discover the race-based cost disparity in adoption. Maria, an adult adoptee posted this in an adoption Facebook Group:

When my parents said they chose me, I sort of imagined a catalog full of beautiful babies but I was the most beautiful, the best one, and they picked me. But when I was a freshman in high school I got into a stupid fight with my mom over nothing and was saying really mean things to her just because I was mad, and I yelled at her that I bet she was sorry she chose me and she flashed back saying they didn’t choose me, I was just the cheapest option. She’s apologized a million times but I am 37 years old and every time I pick up a menu I look at the cheapest entrée and think, that’s me. I am just the cheapest thing on life’s menu.

When adoption is treated like a marketplace, driven by supply and demand, every child in the process has an assigned price, based on what the market will bear. It’s little wonder that some adult adoptees refer to adoption as a form of human trafficking. What does it mean for Black adoptees when adoptive parents are incentivized by discounted prices to adopt them? What does it mean for them when their parents are incentivized to be, as Collard-Wexler put it, indifferent to race? Some adoption activists suggest that a better economic model might be to set adoption costs based on potential adoptive families’ income levels, instead of pricing out children by race. Others want to see adoption costs regulated, with a standardized set of fixed costs that are the same regardless of the child, to eliminate the marketplace effects in the adoption constellation. However, one thing is abundantly clear: something has to change, so that we stop devaluing the lives of Black children in the adoption process.