On Your Feet Foundation does not take a position on adoption. However, we do advocate for ethical adoption practices through Activism in Adoption. As long as adoption exists, we must work to ensure that every adoption is ethical and that every expectant parent and birthparent is treated with dignity and respect, which includes having full knowledge of their rights and options. Ethical adoptions help to ensure better outcomes for all members of the adoption constellation.

We know that one of the main reasons birthparents choose to place their child for adoption is lack of access to the resources necessary to parent, which is a polite way of saying financial insecurity. Money is a taboo subject in the adoption landscape: it isn’t polite to talk about how money changes hands as part of the process of children changing families, or what the inequity in financial resources between adoptive parents and expectant parents means. We don’t say the quiet part out loud: that when expectant mothers are told potential adoptive parents are a ‘better’ choice to raise their child, that is code for they have more money, more access to resources, and less financial stress. We don’t talk about how little money it might take for successful family preservation. But mostly, we don’t talk about the different ways adoptive families are compensated financially for adoption, while at the same time, birthparents were unable to access the resources that would have enabled them to parent their child.

If you’ve ever looked up adoption costs in the US, you’ve very likely had a moment of sticker shock. According to the Child Welfare Information Gateway from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, average costs of adopting a child in the United States range between $20,000 and $45,000. It’s a big check to write, and even if the entire amount isn’t due at once, many families interested in adoption can’t swing the cost upfront without help. And it’s important to understand how many different avenues of help already exist for potential adoptive parents, in order to fully realize how problematic the adoption tax credit is, and how much it tips the scales in favor of adoption over family preservation. So how can adoptions be funded? What help exists for hopeful adoptive parents, that does not exist for expectant parents who do not have adequate resources to parent their child?

GRANTS: A number of non-profit organizations exist to provide grants to potential adopters, in order to cover their adoption costs. While these grants can range in dollar value, the upper limit number seen most often sits between $7,500 and $15,000 which is a substantial amount of total adoption costs. A quick Google search pulls up an easy dozen non-profits who provide grants to hopeful adoptive parents on a continuous rolling basis, and there are no restrictions on how many different grant-making agencies families can ask for help.

CHURCH ADOPTION FUNDS: Many religious institutions maintain funds to help church members adopt children, often referring to it as a call to adopt, positioning adopting a child as a form of ministry. Church members can apply directly to their home church to access funding.

LOW-RATE ADOPTION LOANS: Did you know that there are financial institutions that provide low-interest loans for hopeful adopters? Many of these institutions link adoption to a calling, and provide excellent loan rates. Other institutions provide low-interest loans for adoption.

CROWDFUNDING: GoFundMe, one of the most recognized crowdfunding platforms, has a checklist for adoptive parents to help them fund their adoption. AdoptTogether is an adoption-only crowdfunding platform, which boasts that, “in the past 10 years, we’ve helped over 5,000 families raise over $28 MM to adopt children from 67 countries."

ADOPTION BENEFITS FOR MILITARY PERSONNEL: Military service members who adopt a child under 18 years of age may be reimbursed qualified adoption expenses up to $2,000 per adoptive child (up to a total of $5,000 if more than one child is adopted) per calendar year.

WORKPLACE ADOPTION BENEFITS: To create a family-friendly environment and maintain a competitive benefits package, employers can offer adoption assistance to their employees. Offering adoption benefits is one way employers retain and attract diverse talent, by supporting different paths to parenthood and appearing family-friendly. These benefits include financial support and paid leave.

Typically, adoptive families will tap into a variety of resources to cobble together the full adoption fee, using a mix of savings, grants, loans, family help, crowdfunding and workplace benefits.

"I had no idea how we could pay for this,” one adoptive parent in an adoption Facebook group wrote. “until one Sunday our minister announced that the Board of our church had prayed on it, and decided to donate a percentage of that day’s collection plate to our adoption fund. After services, people we’d never even met were walking over to us, handing us even more cash and congratulating us on our adoption calling. By the end of the afternoon, we had enough to fully fund our homestudy, more than half our agency fees, and a cushion towards the next set of adoption expenses. Our pockets were filled with crumpled-up $20s and $100s. It got the ball rolling, and then we won a grant we had applied for, and then when we were a little short at the end we crowdfunded among our family and friends. I don’t think we were out of pocket more than a thousand dollars for incidentals."

Except they weren’t out of pocket a dime, thanks to the US Tax Act’s adoption credits. In fact, adopting a child may have even made them money, because the adoption tax credit is not a deduction: the credit is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in the amount of federal tax liability owed for the year. The US Tax Act compensates adoptive parents – in both domestic and international adoption – providing them a multi-year tax credit designed to defray adoption expenses.

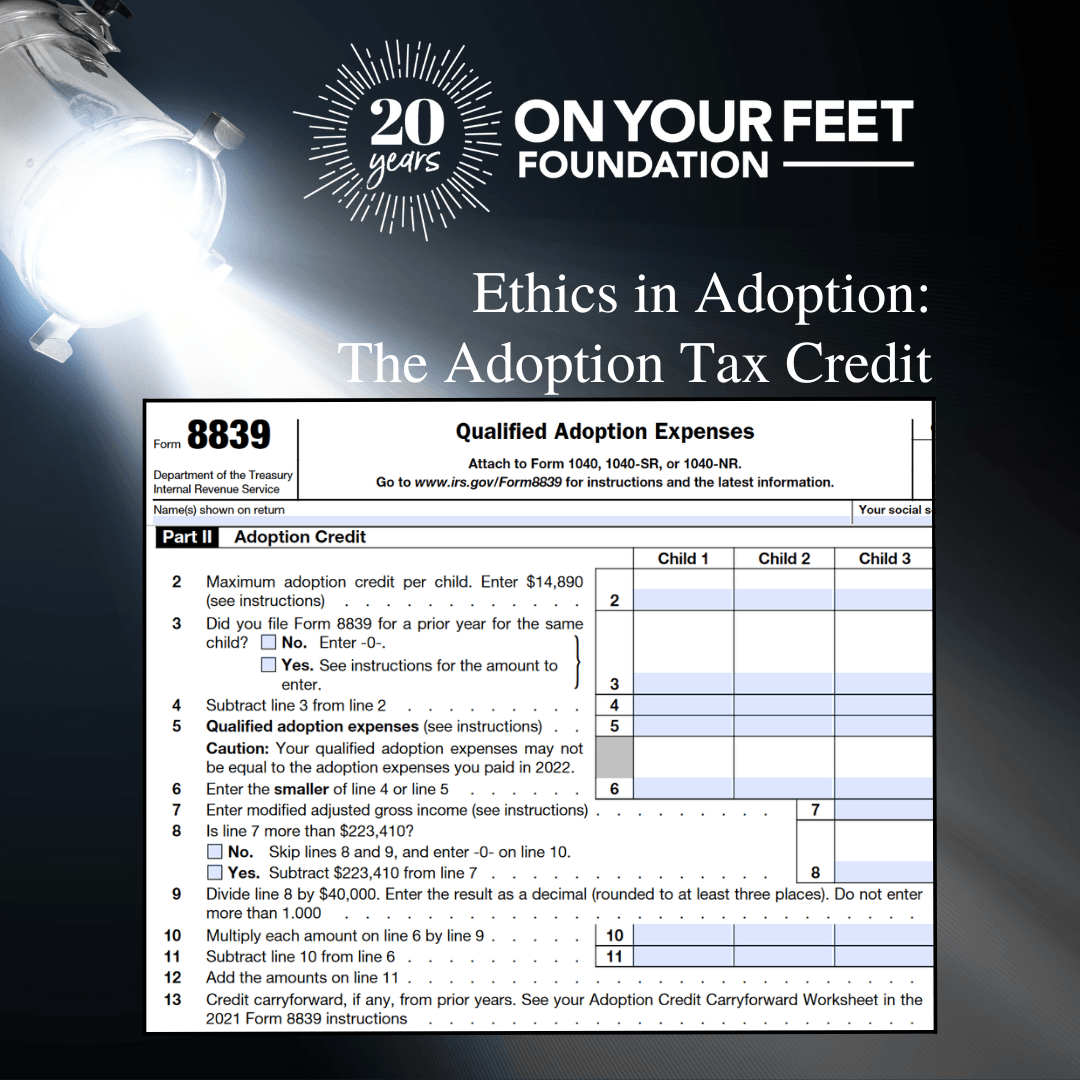

According to the IRS:

This benefit begins to drop once your modified adjusted gross income hits $223,410, and is phased out entirely once your gross income tops $263,410. But if your modified adjusted gross income is less than $223,410 that year, and you either adopted a baby or had an adoption ‘fail’ (a concept we will be discussing in another Ethics in Adoption post), the expenses you paid are covered by this bit of tax code, and that adoption credit can be applied to your tax liability. Even those who normally get a refund may still have tax liability; with the adoption tax credit the taxpayer could get a larger refund.

Not a tax expert? Here’s a quick and dirty explanation: if you adopt a baby, and after doing your taxes that year, find out you owe $5000 in taxes, your adoption tax credit can zero out that amount completely. Now you don’t owe federal taxes. And because you only used part of the total adoption tax credit, you can carry forward the balance you have left on your adoption credit – in this case, $9890, to next year, or the year after that, and if you paid taxes from your paycheck, you may end up being refunded what you already paid, as part of your adoption tax credit. Plus, you are also receiving the tax advantages of claiming a new dependent child.

And what constitutes an adoption expense? The obvious expenses are agency fees, homestudy fees, court costs, and attorney's fees. Less obvious are expenses such as traveling to adopt a child: hotel, airfare, meals, and all travel expenses count for the tax credit. Any expense that you can reasonably argue were incurred and are directly related to and for the principal purpose of the legal adoption of an eligible child are eligible. An expense may be a qualified adoption expense even if the expense is paid before an eligible child has been identified.

As for the adoption credit, it is per child. For a multiple birth adoption, the credit is multiplied by the number of children, even though adoption costs are not multiplied. While some fees may increase slightly - legal filing fees for two instead of one child, etc - overall, multiple birth adoption isn't much more expensive than single birth adoption, but adopting twins brings with it a $29,780 total credit, which, again, can be spread out over up to five years of filing.

When thinking about how the adoption tax credit works, it’s important to note as well that there is no federal oversight in domestic adoption. Every state makes its own rules; has its own guidelines; operates independently of other states and their statutes. However, through implementation of the adoption tax credit, the federal government does fund adopters, giving them tremendous financial advantage over expectant parents experiencing a crisis pregnancy. In an already inequitable situation, the adoption tax credit is the government putting its thumb on the scale, tipping the balance in favor of adoptive parents by absolving them of paying the $14,890 in taxes they would have otherwise owed, and providing that credit for families earning well into six figures annually.

We aren’t here to debate the intricacies of the tax code – we aren’t lawyers or accountants – however, earlier we asked what help exists for people hoping to adopt, and now perhaps the better question is, why does this help exist? Or perhaps, a better question might be, why isn’t there equal help for both potential adoptive parents and expectant parents? Adoptive parents can double-dip – crowdsource their expenses and then take the tax credit – but ask yourself this: where was any of this help for the expectant parents? If parents place their child for adoption because of financial insecurity, raising $20,000 to help them through the first year of parenting and get them on their feet financially is an excellent family preservation tactic. Giving them tax incentives to parent, independent of the tax advantages of claiming a minor child, in the same way we give tax incentives to adoptive parents, would help, too. Ethical adoption practices must always put the needs of the child at the center of all decision-making. What is best for the child should be the consideration that drives adoption. When the federal government does not regulate domestic adoption, but does favor adoptive parents over expectant parents by offering financial incentives for adoptive parents only, that is an inequitable balance of resources that doesn’t feel even remotely ethical.